Candle Of Hope

I met Henry Norman "Nonny" Dagon and his wife Lorraine at their home in East Hartford, Connecticut. It was a warm, beautiful New England day. Shadows cast by big new leaves from the maples rippled on a dark green lawn. The porch was cool. I knocked, and there was Lorraine, welcoming me into their home.

I stepped in and breathed a scented freshness. I asked Lorraine what it was, and her eyes smiled: "That's my Yankee candles. Always have 'em."

Nonny came up to me and gripped my hand firmly. He was young looking for a 71-year-old. He didn't look like he'd lost much weight. As his story unfolded, I learned that there was much more to Nonny, not just physically, but as a man.

Nonny grew up in the East Hartford area. He's lived in Connecticut all his life. There's a hint of Irish brogue in his speech. The shamrock next to his surname on the stone in front of his house proclaims his Irish heritage.

Lorraine is the only woman Nonny has ever wanted. They were childhood sweethearts. They married in 1947, after Nonny finished a two-year stint in the Navy.

To say Nonny Dagon worked hard all his life doesn't do the man justice. He insulated pipe full-time for over thirty years as a member of Local 33 of the Asbestos Heat and Frost Insulators of Wallingford, Connecticut. That would be enough -- no, too much -- for most of us. But during many of those years Nonny also worked a 40 hour week, graveyard shift, as a police officer with the East Hartford Police Department. Ask Nonny why he worked so hard, and he'll smile and tell you why: his family.

"This is my crew," Nonny beamed. "Beautiful children." Looked like five football players and three miniature Lorraines to me.

Nonny enforced the law, and he abided by it. He worked hard to provide for his family. The money was good from insulating pipe and boilers. After a few years, Nonny got his mechanics card, so he could do jobs himself. He worked in factories, at schools, in powerhouses, wherever there was a job that required asbestos insulation, just like his union brothers from Local 33 -- jobs that put food on the table for families, but with a hidden and tragic price.

He didn't just provide for his family, he nurtured it. He did the things with his sons that good fathers do, hunting and fishing and swimming and water skiing and playing ball.

Two of Nonny's sons (Tommy and Ricky) followed in his footsteps as an insulator out of Local 33. Nonny says, "At Montville Power House, I put it on, and Tommy took it off." I asked him how he feels about that now, and Nonny emphasizes, "I feel bad now, but at the time he went in there it was a good paying trade. The asbestos companies made it sound like asbestos was a magic mineral." Yes -- Owens Illinois and Owens Corning both advertised Kaylo pipecovering as a "non-toxic" product that even promoted "worker well-being." A few decades later, Nonny Dagon's tumors are the result of such fiendishness.

After all those years of insulating and serving as a police officer, Nonny finally retired, in a sense. Their eight children had given Nonny and Lorraine fourteen grandchildren and one great-grandchild, and there were babies who needed sitting, who needed to have their strollers pushed up and down the street, and one granddaughter needed a log home to be built, and Lorraine needed a carport to be built . . . and so on. There was never enough time in a day for a man who always felt he could do more for his family.

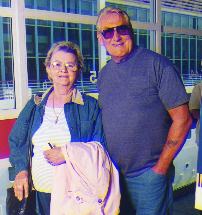

Another picture, of Nonny and Lorraine getting ready to board a cruise ship for Alaska in 1998. Looked like another brilliant day, but Nonny looked younger, and bigger -- his neck and biceps bulging out of his t-shirt, the left forearm popping with muscle. I glanced from the photo to Nonny as he was sitting on the couch, our eyes met, he saw what I was thinking, and we understood each other. He smiled sadly, and said, "You know, I've lost 40 or 50 pounds."

Nonny first noticed his health changing around Christmas. He was tired, and started losing weight. His doctor thought Nonny had an intestinal blockage, and scheduled exploratory surgery to remove the blockage. During surgery on April 16th, Nonny's surgeon found extensive tumor in the peritoneum, tumor which had not been evident on x-ray and CAT scan. The surgeon took biopsy material and sewed Nonny back up. He advised the Dagons that Nonny would have to have chemotherapy.

Nonny returned to his surgeon on April 23rd. The pathologist confirmed a diagnosis of "mesothelioma". Nonny and Lorraine had never heard of such a thing. The Dagons were referred to an oncologist.

At this time, one of the Dagon's adult children searched the internet, and found Roger Worthington. Roger quickly forwarded to the Dagon's a wealth of information on treatment options, including the names of Dr. Robert Taub and Dr. John Chabot, surgical oncologists at Columbia University Medical School in nearby New York City. Both Dr. Taub and Chabot specialize in peritoneal mesothelioma cases.

Armed with this information, the Dagons went to their local oncologist, who said that Nonny had three options: a) do nothing; b) receive chemotherapy; or c) pursue "aggressive" chemotherapy. The Dagons mentioned Dr. Taub, and the local oncologist replied, "Where you'd get his name? He's very good. I do not do radiation therapy, and chemo alone won't even touch this." Nonny's local doctor was refreshingly honest.

The Dagon's met with Dr. Taub, who in turn suggested that his colleague Dr. Chabot perform the de-bulking surgery, which was scheduled for May 28, 1999. Dr. Chabot gave the Dagons hope that he could debulk the tumor so that adjuvant or post-surgery chemotherapy could attack any stray malignant cells. Once the surgery was scheduled, Nonny's legal team scrambled to schedule his deposition and videotaped trial testimony before surgery, in case there were complications during surgery. (At the discovery deposition, the asbestos manufacturers' attorneys question the plaintiff, but on the videotape, the plaintiff's attorney questions to preserve the plaintiff's testimony for the jury.).

Nonny underwent surgery with Dr. Chabot at the Columbia Presbyterian Hospital in New York City as scheduled. Sadly, the tumor had spread to Nonny's liver, and Dr. Chabot was unable to perform further surgery. Nonny suffered greatly after surgery, and was hospitalized for nine days, but his strength and resilience continue to amaze all. He is currently scheduled for chemotherapy. His doctors hope to use adriamycin and cisplatin in Nonny's regimen.

If beating mesothelioma was simply a matter of will, if there was any relationship between a cure and the patient's history of good deeds, or if a family's love was the magic antidote, then Nonny Dagon would be fishing right now or swimming with his grandchildren. There is no question Nonny is a strong man blessed with a strong and loving family. I saw evidence of this strength at Nonny's deposition and videotaped trial testimony, just days before his surgery.

It had been just a few weeks since I had first seen Nonny. He had aged visibly during that short span, and he struggled during the grueling discovery deposition. He seemed groggy, and was grasping at facts that were at his beck and call just weeks before.

After the deposition, I asked Nonny if he could tough it out and go without pain medication for his videotaped trial testimony the next day. Nonny said he'd do it, he'd forego the pain medication, for his family.

On videotape, Nonny described his working conditions and many of the asbestos products that he worked with. He spoke movingly of the day of the shocking diagnosis, of his concerns for his family, for his wife. He spoke of how most of his former co-workers at Local 33 were dead, from asbestosis, or cancer, of how he was one of the few left.

The defense attorneys tried to shut him down. Their clients, the asbestos manufacturers, don't like to hear what men like Nonny have to say. But like the man he is, Nonny Dagon endured the physical pain so that he could set the record straight. We can only hope that, one day, a young businessman might read Nonny's story and take a stand against any corporate policy that elevates quick profits over human lives.

Henry "Nonny" Dagon is the Yankee candle and we pray that he continues to bring light into the darkness.

*** POSTED JUNE 22, 1999 ***

Mr. Henry Dagon passed away on November 3, 1999