Standing Strong Against Mesothelioma

All Systems Go!

In one hour, 68 year-old Kermit Kelley was about to undergo life-altering surgery. It was nine a.m. in the pre-op staging area at UCLA's David Geffen School of Medicine. A steady stream of nurses and doctors had been visiting Kermit since seven o'clock, hooking him up to this, inserting that.

Since his diagnosis with malignant mesothelioma in July, 2007, Kermit and his wife Kerry had pored over the medical literature. They asked all the questions: Should he have chemotherapy? If so, when-before surgery or after? Should he even have surgery? If so, what surgery? The extra-pleural pneumonectomy (EPP), in which the diaphragm, tumor and lung are amputated? Or the pleurectomy / decortication (P/D), in which the doctor removes only the tumor and spares the lung?

Sifting for a solution

The answers were not clear cut. "We knew that lots of doctors liked the EPP," said Kerry. "But we hated the idea of losing Kermit's lung. Why take out the lung if it's healthy and free from cancer? It just didn't make any sense."

The Kelleys learned that the EPP was widely considered to be the surgical standard of care. "Sure, it's the standard," said Kerry. "But what does that mean? The standard for every breast cancer used to be a radical mastectomy, and now we know how wrongheaded that was. I'm no doctor, but I've got common sense, and some things just don't feel right."

They knew that neither operation would cure Kermit's mesothelioma. Both operations, even if performed by a world-class surgeon like Dr. Cameron, would leave microscopic malignant cancer cells in the chest cavity. They learned that recurrence was virtually certain, that it was a matter of "when" rather than a matter of "if."

"Then we found out that the EPP can sometimes actually speed up the spread of the disease. That really scared us. Why would we do a surgery that takes away a healthy lung and helps the cancer grow in other parts of his body? It didn't add up."

The Kelleys were troubled that if they had the EPP, the risk of cancer spreading might increase, since the surgeon typically removes the entire diaphragm, a cutting process which can create holes through which malignant cells metastasize elsewhere by spilling into the peritoneum.

Since the tumor's recurrence is a virtual certainty, what if it cropped up in the only good lung after the other lung had been removed? What then? The evidence began to tilt in favor of Dr. Cameron's pleurectomy / decortication.

Straight talk

Encouragement.

Dr. Cameron advises Kermit of test results showing the tumor had encased the lung and locked up the diaphragm. Game plan: liberate the lung, restore normal lung function.

The Kelleys consulted with Dr. Robert Cameron, director of the Mesothelioma Program at UCLA.

"I liked him right away," said Kermit. "Forthright. No sugar-coating. Compassionate. Objective. A man you can respect after the first five words come out of his mouth."

Adds Kerry, "Dr. Cameron didn't promise a cure or tell us that his surgery was always better than the EPP. He laid out the facts-because of all the other parts of therapy and other factors and such, you can't scientifically say one is better than the other. But he did say he would try to buy us some time."

If the surgery succeeded, the post-operative period would allow them to also pursue complementary therapies such as immunotherapy with interferon alpha. Dr. Cameron explained that the published survival data did not clearly favor the EPP over the pleurectomy. He advised that more articles were being published that questioned the presumed merits of the EPP over the P/D, much as surgeons years ago began to question and later discard the strategy of performing a radical mastectomy for every breast cancer.

The Kelleys were also impressed with quality of life issues after the surgery. "I've got a good heart, but I was concerned about putting more stress on my ticker if I only had one lung," Kermit said.

Kermit, a career water works contractor in the public and private sector for over thirty years, knew the value of hard work. "Sometimes doing the job right means working harder and longer. You know that on the job site, but you don't ever think about it like that with surgeons. You know, it's true. Sometimes the difference between doing a good surgery is kind of like doing a good piece of carpentry, the guy who is more patient and has more experience and knows his tools better and knows his wood better is the guy who does the better job. You don't think of working on a lung the same as working on a cabinet, but I suppose when you get down to it, maybe it is."

The Kelleys learned that the EPP was a simpler procedure that took 3-4 hours, whereas Dr. Cameron's surgery was more complicated, and often took 4-9 hours, depending on whether the tumor had invaded the chest wall, heart sac, or diaphragm. Kermit read that each procedure cost about the same, but that Medicare paid the surgeon more for the easier EPP than for the longer, more arduous P/D.

Crossing the Rubicon

"That did it for me," Kermit said. "Dr. Cameron is willing to work twice as long for less money because he believes the pleurectomy is the way to go. If I'm going to let a doctor stick his hands into my chest, I want the hands of a skilled craftsmen who's not afraid of hard work. That's how I was raised."

Kermit decided that he could more effectively pursue the healing process with two healthy lungs rather than one, quarterbacked by a doctor who was not afraid of a hard day's work, who was an expert surgeon, and who was committed to helping his patient from start to finish. "I didn't want a surgeon who would cut and run. I know this is a long haul. I wanted a doctor who would help us with options after surgery."

Adds Kerry: "We believe it all came down to quality of life. With two healthy lungs he has a better chance of recovering from the surgery and has a better chance of living a high quality of life.

A tumor that slowly suffocates

Thoracic surgery is one of the surgical specialties whose practitioners are often regarded with awe. These are the men and women who operate on and around the heart and lungs, the organs that more than any except the brain symbolize humanity and life. The P/D begins by cutting open the chest, clipping out a rib, and spreading open the chest wall.

In a healthy person, such a procedure would reveal the lung and diaphragm, working together to pump air into the oxygen-hungry body. But in Kermit's case, the open chest revealed a smooth, red, thick rubbery blanket that encased the entire lung and stuck like cement to the chest wall.

The massive mesothelioma tumor had grown around his lung, compressed it, and finally collapsed it. He had only one lung working now, and the void in his chest testified to the power and destructive force of the relentless tumor.

Stripping away the serpent

Dr. Cameron first explored the extent of the tumor with his hand, inserting it into Kermit's chest. Although the PET scan had depicted the tumor as small to moderately sized, reality proved far different. As it slowly strangled his lung, the cancer had also latched onto the lining of his heart and his diaphragm. Inveigling itself with a complex network of veins and arteries, the giant tumor had positioned itself so that removing it might be more dangerous than leaving it alone.

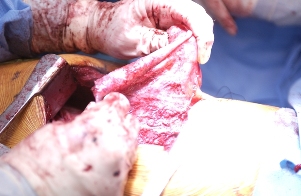

The devil by its horns.

After stripping the tumor off the chest wall and lung apex, Dr. Cameron holds a flap of tumor. Fours hours to go.

It became clear in an instant why so many surgeons prefer the EPP and eschew the P/D: patience and skill. Working the tenacious and deadly tumor away from the organs and arteries had to be done millimeter by millimeter. The patience, concentration, and methodical repetition required to strip away the cancerous blanket are monumental. It takes all of that, plus nimble fingers, which are probably the surgeon's best tumor-stripping device.

Uncertainty was another factor. What if after all the hard work of chiseling the tumor off the chest wall and diaphragm it turned out the tumor had trespassed - i.e., contaminated - the actual lung lobes? If the surgeon simply amputated the entire tumor-encoated lung, without daring to strip it off, and it later turned out the lungs were tumor free, well, by that time it would be too late. More risk, more tedious labor were the only certainties. But, with all big risks comes great pay-offs.

Dr. Cameron's legendary stamina was evident after the first few hours passed. Never leaving his patient's side for even a second, he carefully and laboriously performed his delicate work. As other members of the surgical team finally succumbed to fatigue or shift's end, Dr. Cameron remained at the helm of his ship, calmly, patiently, firmly guiding the hulk of his surgical team to its final destination: peeling away the cancer within.

Dr. Richard Peng, an enormously talented young surgeon from Orange County, worked in tandem with Dr. Cameron, following his guidance and working with extraordinary care and precision within the narrow confines of the chest cavity. Dexterously using his surgical tools as he sutured together a patch of bovine diaphragm to replace the pieces of diaphragm lost to the tumor, Dr. Peng displayed the same level of focus and complete absorption as his mentor. They had to, as stripping away tumor off of a 2 mm thick sheet of muscle is like cutting glue from the surface of a balloon without puncturing it. Dr. Cameron and Dr. Peng were well aware of the risks of nicking the diaphragm and thus providing a portal through which the malignant cells could travel to the gut.

The beating heart

Dr. Cameron holds the thick, rubbery tumor after meticulously scraping it off the thin diaphragm muscle.

Kermit's tumor, however, had decided to throw Dr. Cameron a curve. In addition to its insidious growth along the lung and diaphragm, it had snaked its way up to the pericardium, the delicate sac that encloses the human heart. Removing the tumor without damaging the pericardium was crucial to keeping the cancer off of the heart. In a worst-case scenario a patient can live with only one lung-the same can obviously not be said for the heart.

By now the operation was six hours long, and at a time when most people would collapse simply from having to stand in one place for so long, Dr. Cameron was just as focused and fresh as the moment he'd begun-never mind that he had left the operating room the prior evening at midnight. Never moving from his patient's side, he and Dr. Peng carefully began what can only be described as a procedure that is delicate beyond belief.

The attempt succeeded, and the heart was safe.

The home stretch

A full seven hours into the surgery, Dr. Cameron moved to the final part of the operation: removing the tumor from the lung itself. This part of the surgery has often been called "impossible" by experienced thoracic surgeons, since the tumor creeps down into the deep folds and fissures that separate the different lobes of the lung. With a smile, Dr. Cameron showed the "impossibility" of this aspect of the surgery, using the most sophisticated and delicate instrument ever created: his index finger.

Gently moving his finger into the fissures, he easily lifted out the tumor. Soon enough the entire cancer was peeled back like the diseased rind of an orange and removed from Kermit's chest. Beneath the cancerous blanket lay a big, pink, healthy lung, waiting to step up in its lifelong service to the body's blood. With a twist of the anesthesiologist's knob that poured life-giving oxygen into the collapsed lung, the lung filled with air and swelled up to recapture its former space within the chest.

Dr. Cameron watched for a moment, and then said with a smile, "Look at that. A perfectly good lung. Why would anyone want to cut that out and throw it away? I think it looks pretty good right where it is."

About nine hours after opening up Kermit's chest, Dr. Cameron and Dr. Peng removed the four-pound tumor in one piece from the cleaned up chest cavity. "Fruits of their labor?" Not exactly. The fruit of their labor was still inside Kermit's chest, where it belonged, a pink plum of a human lung, ready to return to action. Not a bad pay-off for a few extra hours of hard labor, especially for Kermit and his family.

Mesothelioma patients giving back

Kermit's desire to educate patients, doctors, and the world about mesothelioma and its treatment is a common thread that runs among victims of asbestos poisoning. John McNamara, a mesothelioma survivor like Kermit who was also treated by Dr. Cameron, decided that he would lend a hand as well. John and his wife T.C. bought an apartment in Los Angeles, furnished it, and made it available to any mesothelioma patient seeking consultation or treatment from Dr. Cameron.

This generous donation made the Kelleys' initial visit and surgery in Los Angeles possible. Generosity tends to spread. Like the McNamaras, the Kelleys before and after the surgery expressed their wish to help educate others about Dr. Cameron's surgery. "We'd like others to know about the surgery," said Kermit, who agreed to having his surgery photographed. "I don't think of myself as either a 'guinea pig' or a 'trailblazer.' I'm just a guy who's making the best of a bad situation. I've learned a few things from patients before me, and I hope to contribute my own story."

Working together, and coordinated through the Pacific Meso Center, the McNamaras and Kelleys have helped turn another page in the treatment and education about this disease.

*** POSTED OCTOBER 8, 2007 ***