A Candid Interview With Barbara McQueen

In 1980, at the tender age of 50, after pursuing "alternative remedies" south of the border, McQueen died from malignant mesothelioma. Steve McQueen is easily the most famous person whose life was cut short by asbestos-induced mesothelioma. However, 25 years after his death, few people outside "Club Meso" associate the rare cancer with the "King of Cool." Neither Steve, nor his wife Barbara, were eager to invite the world into their hospital or living room during their ordeal. A lawsuit was never filed. As a result, questions like: what cancer did he die from (was it "lung cancer" or "mesothelioma") and what caused his cancer (was it asbestos? And if so, where was he exposed?), have continued to both evade easy answers and stimulate ponderous speculation.

Last year, to commemorate the 25 th anniversary of Steve McQueen's passing, I made a donation to mesothelioma medical research in Steve's name. It made sense. My wife and I allowed a Hollywood movie production to film a few scenes of a soon-to-be released movie at our house in Dana Point. Out of curiosity, I asked several of the producers and actors whether they knew that Steve McQueen died from mesothelioma. Nobody knew it. All of them thought it was your garden variety lung cancer caused by smoking. We decided to donate the "location rental fee" to mesothelioma research, partly to help clear the record that it was asbestos, not cigarettes, that claimed Steve McQueen's life.

A few days later, out of the blue I got a call from Barbara McQueen. I had heard that the former model was something of a recluse, who essentially split from the Hollywood scene after her husband died. Barbara called to thank me. Over the next several months, somewhat reluctantly at first, Barbara and I talked over the telephone about her experience with Steve in the final months of his life. Barbara had never granted an interview before, with the exception of an interview she gave to a Japanese television station, which aired a documentary about Steve on the 25 th anniversary of his death.

Barbara did not call me because she wanted publicity. Far from it. Even before she married Steve she preferred the quiet of the desert to the hustle and bustle of Hollywood. Then and now, she prefers to be left alone. She certainly does not think of herself as a "do-gooder" or "crusader," but I'm guessing she decided to speak up because she genuinely was both incredulous and angry that so little has been done since her husband died 26 years ago to prevent, treat, and cure mesothelioma.

What follows is our interview, pasted together from several conversations. The written words do not do justice to the snap, crackle, and pop of Barbara's delivery. She loves to laugh and wax wacky (her answering machine message manages to reference both Elvis and her abduction by space aliens). She tends to look at the bright if not goofy side of life, but when the subject turned to the last few months of Steve's life, there's a sense of dread in her voice, like she's having to dredge up memories that she's tried very hard to suppress for the last 26 years.

RW: It's now been over 25 years since Steve McQueen died from malignant mesothelioma. Take us back to the time before his diagnosis in late 1979. What was his health like?

BM: Uggh. That was a long time ago. It was like a blur. I try not to think about it much. It was such a bewildering time. Actually it was awful. He was always such a hunk. He took care of his body religiously. We first met in 1977. He'd get up early and do his martial arts-he was a black belt in karate. He was supposed to keep that secret from the movie people. They were always worried he'd hurt himself.

RW: So what prompted Steve to seek medical care in 1979?

BM: Well, during the shooting of Tom Horn, we noticed he wasn't feeling as perky. Sort of lethargic. Normally, Steve was a high energy guy, always busy with his motorcycles, planes, martial arts or whatever. Then he started getting tired and short of breath. That was in early 1979. He started having night sweats during The Hunter, his last movie.

RW: What did he do about it? Did he see a doctor?

BM: Steve was a tough guy. He had a high tolerance for pain. He didn't talk about it. Finally, his breathing got so bad he went to a doctor in Santa Paula who took chest films and found some spots.

RW: Did you or Steve suspect anything serious, like cancer?

BM: Not in a million years. He was young, healthy, and full of vigor. Hunky (laughs). By the way, when I first met Steve, I didn't even know who he was. I never thought of Steve as the actor. He was a regular guy, deep down, not a big conceited Hollywood idol.

RW: What do you remember about the day he was diagnosed, which I've read was around December 22, 1979?

BM: We had been referred to Cedars Sinai Hospital in Los Angeles. They wanted to take a look under the hood, so to speak. I was in the waiting room with friends. The surgeon, Dr. Gold, came out and told me they found a bunch of tumor in his right lung. At first I was in shock. How could this happen? Then I started crying my eyes out.

RW: Did Dr. Gold tell you the tumor was " mesothelioma?"

BM: Yes, then or sometime later. I had no clue what that was. I asked him whether it was curable. He said it wasn't curable and really not even treatable. We were stunned.

RW: Did the doctors talk about Steve's prognosis?

BM: They split us apart on that. They told me that Steve had at least 4 to 5 years to live. But they told Steve, I learned later, he only had a few months. Later on, I saw Dr. Gold and I asked the SOB why he told me Steve had years to live. He said he didn't want to "freak me out."

RW: There's a lot of mythology surrounding Steve's diagnosis. One rumor is that Steve's mesothelioma started in his stomach linings. Was that the case?

BM: Not that I'm aware of. They found it first around his lung. It wasn't until a few months later that the tumor spread to the stomach. He also had a bump on his neck, which was the cancer.

RW: Did the doctors ever ask Steve whether he worked around asbestos?

BM: Sure they did. Steve talked about his racing suits, which were insulated with asbestos. He didn't go into any detail back then. But over time, with all the books written about him, I've learned more about it. In the 1940's, when he was only 16, Steve joined the merchant marines-actually somebody got him drunk and he woke up on a ship already out at sea. They made him swab the decks and clean up the pipes. He was probably exposed there. And then there was the Marine Corps. He blew up a can of beans and they punished him by making him strip the asbestos off the pipes of a ship. That was in the late 1940s. Steve did not talk about it much but I have a tape recording in which he was asked just before he died what caused his mesothelioma. He said: "asbestos."

RW: Did you think about filing a claim with anyone for any compensation?

BM: Not that I remember. We were very private. I had no clue about the law. I'm sure Steve didn't want to answer a bunch of questions about his private life. We were focused on getting well.

RW: What medical options were you given by the Cedar Sinai doctors back in late 1979?

BM: The doctors in LA basically told us to enjoy the time we had left. I don't remember exactly what they said about options. All I recall is that the doctors said surgery was out of the question and chemo didn't really work. It was a rare cancer and all their patients had died. Steve asked me what I wanted to do--should we find some doctors who would fight this thing or just go to the desert until the clock runs out? We decided to fight back. Steve was going to try chemotherapy but walked out when the nurse said the stuff was so toxic it would burn his skin if it got on him. I mean, if it would burn your skin, imagine what it would do to your insides? It sort of scared the daylights out of him.

We went home and Steve went on a huge vitamin regimen. Friends started telling us about various doctors who were offering all sorts of home remedies Since the mainstream doctors were not offering any hope, Steve figured it wouldn't do any harm to look at alternatives. We heard about a guy--I don't know if he was a doctor or not--in San Fernando who was offering mega-vitamins through an IV. Steve decided to try it. I learned to open up a vein for him. The program was sort of shady. We'd sit in a van in the back of a building, in a parking lot in San Fernando Valley, and Steve would get his vitamin chelation, I think they called it. If Steve believed in something, he wasn't going to let the fact that it was not approved by the government stop him.

RW: What was Steve's state of mind like then?

BM: It was good. He had support pouring in from everywhere. Everybody it seemed had the magic cure. He was open to whatever sounded good. He still looked good and wasn't in bad pain. He kept thinking about getting back on his dirt bikes, getting back out in the desert. You know, he was sort of a legend, and there was almost a pressure on him to do something crazy, that whole "live hard, drive fast, and die young" thing. He wasn't a conventional guy who followed the herd and did what he was told.

RW: After Steve's diagnosis, and three years after you first met, on January 16, 1980, you and Steve were married. What was your vision of the future at that time?

BM: We knew about the diagnosis, but we were both optimistic. Steve prayed very hard he could fix the problem. His body was breaking, but his heart and his hope, were strong. From the outside you really wouldn't even know his insides were breaking. He didn't like to talk about his pain, and he didn't like painkillers. We thought he'd get well. We talked about moving to Ketchum [Idaho], having a couple of kids, horses, a ranch. You know, the storybook picture of the wife pregnant in the kitchen, the husband sitting in a rocking chair on the porch, drinking an Old Milwaukee.

RW: Old Milwaukee?

BM: Yes (laughs). Steve wasn't a beer snob. He preferred your basic working man's beer. As long as it was cold. Anyway, we had 480 acres in Ketchum with a creek running through it. We planned to build a ranch house. And an airplane runway. Steve loved flying, and he owned a few old planes.

RW: When the press started reporting that Steve had "lung cancer," did you or Steve ever want to issue a correction that Steve actually had mesothelioma, which was caused by asbestos, not smoking?

BM: We kept everything under wraps as long as we could. Towards the end, Steve's body didn't look good. His belly started bloating out. He lost weight. We needed privacy--it wasn't a Hollywood vanity thing: he had already started retiring from the movie business, and so he wasn't absorbed about his public image. He just didn't want his kids to know how bad things were. He worshipped his kids; he wanted to protect them. As a Hollywood star, he'd been burned by the tabloids before, and he just didn't want anything to do with the media circus. As far as the difference between lung cancer and meso, we really were not clued in to the differences. Cancer was cancer. We were focused on staying alive.

RW: Steve McQueen is remembered for many things, including his decision to seek non-FDA approved treatments in Mexico by a questionable doctor named Dr. William Kelly. We know that Dr. Kelly was in fact a dentist who had his license pulled in 1976. What was Steve's frame of mind when, despite all the black marks in Dr. Kelly's record, he hired him anyway?

BM: That's a tough one. I was 26 years old at the time. Steve was 49. I thought Steve would live forever. I never delved into Dr. Kelly's background. We'd heard that Dr. Kelly had cured cancer in a few patients, and he was something of a rebel. We went to Spokane to interview him. What he said seemed to make sense, but most importantly he gave Steve hope. I think, looking back, as anyone with cancer knows, you reach a point of desperation and start grasping for whatever sounds best. Dr. Kelly tested Steve's blood to determine what nutrients and vitamins he needed. His theory sounded good: detoxing the body and boosting the immune system to fight the tumors naturally. Who can argue with that? We decided to go to Dr. Kelly's clinic in Plaza Santa Maria, Mexico.

RW: What was that like? And what were the treatments?

BM: The clinic was in a remote area. We flew down in Steve's plane. As for treatments, I haven't thought about it much. I remember the veggie juice he was always drinking and the calf liver blood . Yuck. I'm sure you know about the coffee enemas. I don't remember him ever taking laetrile, like some people reported. There was other stuff, too.

The nurses were very nice but Steve drove them crazy. He demanded sweets, which they wouldn't let him have. Finally, Steve convinced them to let him have a chocolate cake, and of course Steve threw a big party. We had a friend fly a cake down every Wednesday. All the patients broke their diets and gorged on cake and ice cream for about an hour. Steve was a big hit with the other patients. That was his "happy thing." But it was a stressful time and we were a little stir crazy.

RW: Did Steve think the treatments were helping?

BM: Steve tried to stay upbeat. He wanted to believe he would get better. And he was a little sick of all the Dr. Kelly bashing in the press. I remember after a month or so we took films which showed the tumor in the neck was shrinking, or so we thought. His belly kept getting bigger, but the rest of him was getting skinnier. The pain was getting worse, the poor guy.

RW: Did Dr. Kelly ever tell Steve that the "non-specific metabolic therapy" treatments were shrinking his tumors.

BM: Dr. Kelly did tell him the treatments were working. God it burns me. I was a young bride, full of hope. Steve was my first true love. Sometimes now I think back that maybe we should've just gone to the desert. Getting eaten by rattlesnakes would've been better. Steve got cheated, royally.

RW: On October 6, 1980, when you were down in Mexico, you read a statement to the public that read: " Steve's great wish is that the United States would allow the medical treatment he is undergoing in this country so we could go home and Steve could continue his program among the people and surroundings he loves."

BM: Yes. The media was hounding us and we wanted our privacy. We wanted to go home. I wrote a letter to Ronald Reagan, the President. I asked him to cut us some slack, let us take the treatments in Santa Paula. I didn't know why it should be illegal for Steve to take holistic medicines. I mean, c'mon, the doctors in Los Angeles wrote him off, told him he had 2 months to live. Rosarita was a beautiful, magical place, but we were living in a trailer and we wanted to go home. I was angry. Steve was suffering. Seven days a week for a solid month, he was taking coffee enemas and the calf liver. He wanted to go home.

RW: Did Reagan reply?

BM: No. I guess he didn't like Steve's movies. (laughs). P.S. I'm a Democrat!

RW: How about you? Did you believe the "non-specific metabolic therapy" was working?

BM: I held out hope. I wanted to return home to be around friends and family, but there was nothing for us treatment-wise in the U.S. We kept hoping it would work, that we would wake up from this nightmare, and he'd be strong again, back on his motorcycle.

RW: After Steve went public with his cancer on October 6, 1980, Dr. Kelly issued a press release a few days later, in which he stated his belief that, "Mr. McQueen can fully recover and return to a normal lifestyle." Did you believe that?

BM: No. I wanted to believe it. But by then I was coming around to the reality that Kelly was a nutcase. I'm not slamming holistic medicine--I'm a vegetarian for the most part--and I'd never look down on somebody who went outside the U.S. for any treatment. I'm sure there are places where cancer patients can get help. But Kelly's clinic was a sham. His optimism was pure bullcorn.

RW: I've read that Steve paid William Kelly at least $375,000. Looking back, 25 years later, do you believe that William Kelly exploited Steve?

BM: $375,000? I don't know if it was that much. But it was all about money for Kelly - Steve McQueen was a big paycheck to him, a celebrity. A bank account. Now it's more easy to see it, but then we were along for the ride. The nurses down there were caring, loving people--fabulous people, and I truly think they wanted to help. But Kelly was better at promoting himself than curing anyone. At the time, like most cancer patients, we would've paid anything for a cure. We were happy to be alive and we wanted more.

RW: By later October, I've read that Steve started a downward spiral. His belly began to distend, he was wasting away and in chronic pain. It's clear from the records I've seen that the mesothelioma had spread to his abdominal cavity. What options did Steve have, if any?

BM: We took a film in late October back at Cedars Sinai. It showed a huge tumor in his stomach. The doctors said they couldn't do anything or operate because Steve was so weak. They were worried about his heart. But Steve couldn't handle it. He wanted to get rid of this, this beast in his belly. We flew to Juarez, Mexico where there was a surgeon who said he would operate.

RW: This is a tough question. I've read that a CT taken just before the surgery in Juarez showed metastatic tumor in Steve's lung linings, inside his lungs, around his abdominal cavity, and there were tumors in his liver and in his pelvis. What was Steve's mindset when he decided to go forward with the surgery?

BM: (Pause) The doctors had washed their hands of him. He wanted to help himself. He wasn't a "poor pitiful me" person. He was either going to sit in bed and die or try something. That's what he wanted to do.

RW: We know that Steve died a day after his surgery in Juarez, Mexico on November 7, 1980. Looking back, are there any parts of the Kelly program that you would recommend to mesothelioma patients (coffee enemas, strict veggie diet, vitamin loading, massage, chelation, detoxification, etc.)?

BM: It's a personal thing. I believe in a veggie diet. Vitamins are great. Granted, I eat a juicy burger now and then. Coffee enemas I never got. I don't know if they ever cleaned anything out, seems like that would just jack you up all night (laughs). I'm for alternative medicines, but that Kelly was just an odd one. There may have been people who came out of there [Plaza Santa Maria] ok, but I'm not sure.

RW: This is sort of a corny question, and I'm not sure you have any answer. But what was your opinion, if any, at the time, of the government's interest in mesothelioma cancer research? Did you have any trouble believing that in our great country, no treatment was available and a cure was simply a pipe dream?

BM: Back then I was too innocent. I had no clue about the government's role. I was always told it was such a new disease that nobody survived and nothing could be done about it.

RW: Let's talk about where we are today, more than 25 years later. This is a long "speechy-type" question so bear with me.

Every year, about 3,000 Americans are diagnosed with meso. About 62,000 Americans have died from mesothelioma since Steve passed away in 1980. Now, about 1/3 of all Americans diagnosed with mesothelioma were exposed to asbestos while serving their country in the military, just like Steve did. Congress has appropriated over $1.5 billion to the Department of Defense to run a medical research program for breast and prostate cancer, neither of which is a "service connected disability." Asbestos-related mesothelioma certainly is a service connected disability, but today, 25 years after Steve McQueen's death, the DOD still doesn't have a program for mesothelioma research. Mesothelioma research continues to be under-funded when compared to other cancers. Meanwhile, the incidence of mesothelioma is not expected to peak in this country until 2025.

That's a load of numbers and statistics. But how do you feel about that? How do you feel about the fact that 25 years after Steve McQueen's death this government still doesn't have any interest in curing mesothelioma, a cancer that's plagued many of our veterans?

BM: I'm angry about it. The government doesn't care. It's outrageous. I know a lot of veterans. They need help.

RW: Let me amplify the point a little more, and bring it full circle.

Steve was exposed to asbestos while in the merchants marines which, during World War II, was a subset of the U.S. Navy. And then he was exposed in the 1950s during his stint in the U.S. Marine Corp when he was forced to strip asbestos lagging off of steam pipes on a Navy troop carrier. Our government has known about the scourge of mesothelioma and its relationship to asbestos since the early 1950s. But the Veterans Administration even today doesn't have a program to treat Navy vets with mesothelioma. Do you think the government has a duty to serve those who served our country by funding research to find a cure?

BM: Absolutely. It's hard to believe that the Government has turned its back on veterans. I never thought about Steve as a "veteran," but I guess he was.

RW: One final "speech-question." It's well known that by 1920 the asbestos companies knew that asbestos fibers could cause disease and death. They knew asbestos could cause cancer by at least 1940, but they continued to produce millions of tons of it through the mid 1970s. Now, it's estimated that every year 10,000 Americans die from asbestos-related pulmonary diseases and cancer. Do you have a message to the companies who made the poison that killed your husband?

BM: [Pause] I really don't want to think about it. It's disgusting! It comes down to money, money, money. I don't know what to say--money can't buy life, love or happiness, but it sure can drive some companies to do terrible things to people.

RW: When you hear the word "asbestos," what comes to mind?

BM: I cringe when I hear the word. In the past few years, I've learned it's everywhere, in our schools, homes, in buildings. Everyone's exposed, not just construction workers. When I bought a house in Montana, I made double sure there was no asbestos in it. We have a place in Montana. I've read there's a huge rash of asbestos disease in a town called Libby. That's where they mined it.

RW: I have a poster of Steve McQueen we made up for a mesothelioma foundation that I helped create [MARF]. The tagline is " asbestos does not respect fame or fortune." The idea is that asbestos fibers do not respect the color of your collar; they'll take down a famous movie star as well as a young girl in her twenties.

BM: That's true. That's about right. I never thought of Steve as a guy heavily exposed to asbestos. But I guess it doesn't take much.

RW: Did you know that today, in 2006, asbestos has not been banned in the United States?

BM: Good lord you're kidding me! What's wrong with our government? How many more have to die before the government wakes up?

RW: It's been nice talking to you Barbara. I want to let you know that things are getting better. In Los Angeles, we've set up the Punch Worthington lab, headed up by Dr. Robert Cameron, who's the Chief of Thoracic Surgery at UCLA Medical School. Dr. Cameron has some great ideas for not only treating mesothelioma but also for reducing the risk for heavily exposed people. It's sort of fitting - 25 years ago, surgeons in LA told you and Steve that nothing could be done. Now, we've got doctors who are ready, willing, and able to grab mesothelioma by the tail and give patients a fighting chance.

BM: That's great. Count me in. Whatever I can do to help.

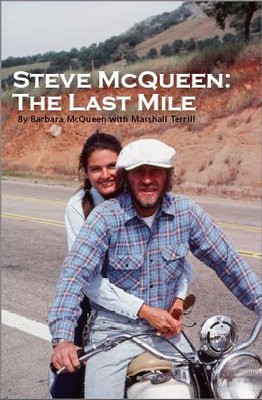

When Barbara and Steve began dating seriously in the late 1970s, she cut a deal with Steve that wherever she went, so did her camera. Barbara, a model by trade, was also a photographer by hobby. Over the course of the next three to four years, she snapped hundreds of photographs. For all these years she has kept her photographs private. Now, Barbara is ready to make many of her photographs public. Together with her good friend and confidante, the author Marshall Terrill, she is soon to publish her photo book: Steve McQueen: The Last Mile. According to their website (click here), the publisher plans to run a limited edition of 2,000 books, which will be signed by both Barbara and Marshall (who in 1993 wrote the excellent biography, Steve McQueen: Portrait of an American Rebel).

The release date coincides with the 26 th anniversary of Steve McQueen's death. According to the website, the book

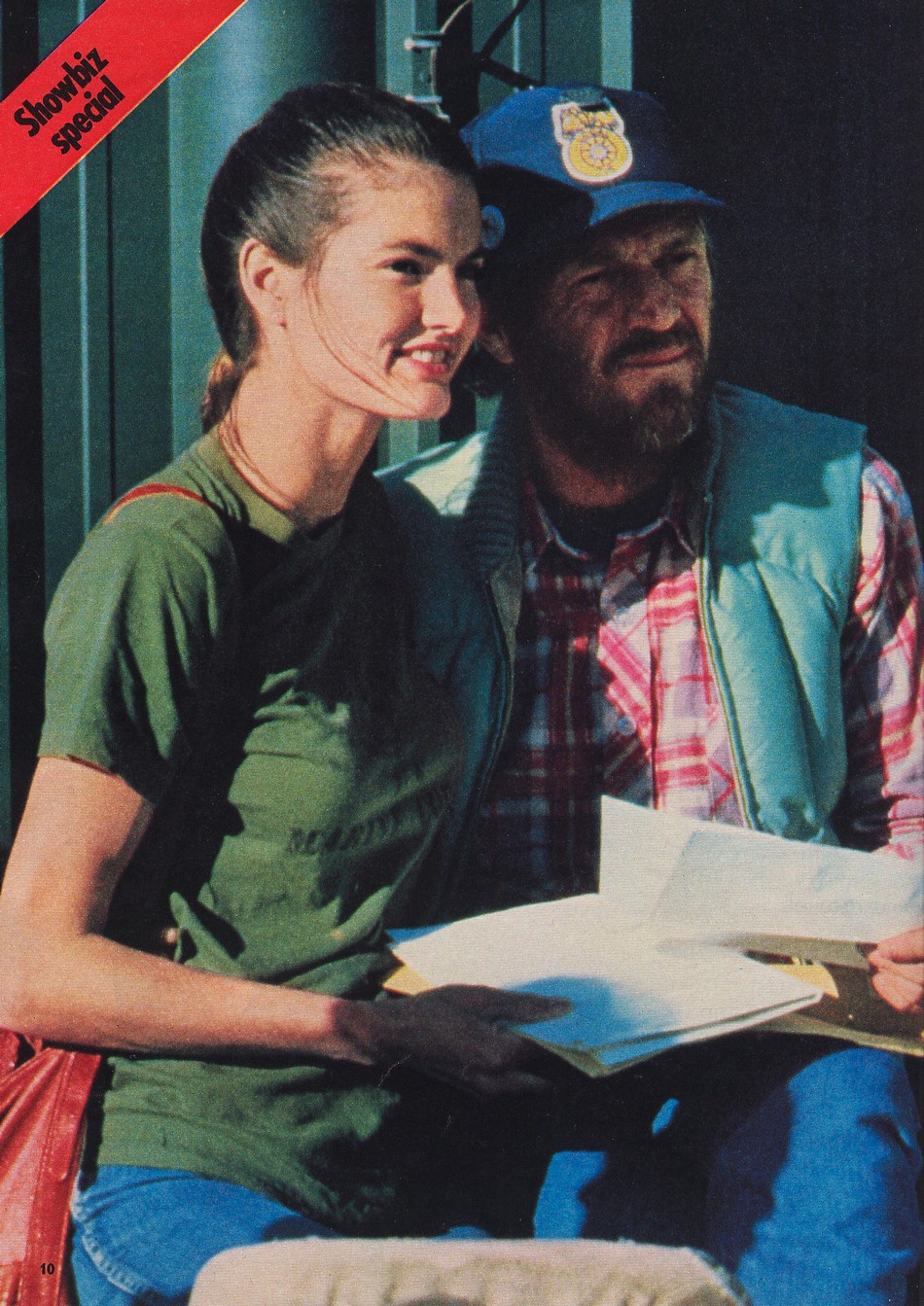

"chronicles Barbara's early history and modeling career; her years with McQueen at Trancas Beach and Santa Paula as well as behind-the-scene photos on the sets of Tom Horn and The Hunter. The book is written in passage form, weaving Barbara McQueen's personal history, her relationship with her famous husband and the stories behind the hundreds of candid pictures she took."

To reserve a limited edition copy of Steve McQueen: The Last Mile, go to www.daltonwatson.com (I have not yet seen the book).

As a lawyer, myself and others have long speculated over where and how Steve McQueen was exposed to asbestos. Steve never testified in a deposition, but he did tell numerous reporters and friends about his asbestos exposure. Before he died, he was asked by a friend, who tape recorded the conversation, how he got his cancer. Steve's blunt answer spoke for itself: "asbestos poisoning in my lungs, which is rare." (Interview with Burgh Joy, clinical professor at UCLA, personal archives of Barbara McQueen, 1980). The following sources further elucidate the details of where and when McQueen was exposed:

1: Sandford, Christopher, McQueen: The Biography, Taylor Trade Publishing, New York (2003).

"Besides the fighting and gambling, Steve's only other long-term legacy from the military was his cancer. The exact illness that led him to Dr. Kelly was mesothelioma, an acute form of asbestos poisoning. In those days the stuff was everywhere, including in the tanks he drove at Camp Lejeune. It was also used for such insulation as there was in his barracks. In one sorry incident (part of a punishment for his exploding a can of baked beans) McQueen was ordered to strip and refit a troop ship's boiler room. Most of the pipes there were lagged with asbestos. The air was so heavy with it, Steve would say, 'You could actually see the shit as you breathed it.'" (page 42).

2. Terrill, Marshall, Steve McQueen: Portrait of an American Rebel, Donald I. Fine, Inc. (1993).

"The cancer is usually caused by asbestos inhalation. Steve recalled later on that his stint in the merchant marines had him swabbing the inside of the ship where the ceiling was lined with asbestos." (page 364). I spoke to Mr. Terrill about the source of this revelation. He advised that in 1991 he had spoken to John Sturgis, the director ( Magnificent Seven and The Great Escape), who recalled a conversation he had with McQueen just after his diagnosis.

3. Spiegel, Penina. McQueen: The Untold Story of a Bad Boy in Hollywood, Doubleday and Co., New York (1986). Excerpt:

"Steve had been peculiarly surrounded by asbestos all his life. It was often present in his place of work during his itinerant years when he picked up odd jobs--at construction sites, for example. Asbestos was used in the insulation of every modern ship built before 1976; it is found on sound stages, in brake linings of race cars, and in the protective helmets and suits worn by race car drivers." John Sturges remembers Steve telling him about an incident that occurred while he was stationed in the Aleutian Island during his stint in the Marine Corps. "Steve had been sentenced to six weeks in the brig. He spent the time assigned to a work detail in the hold of a ship, cleaning the engine room. The pipes were covered with asbestos linings, which the men ripped out and replaced." The air was so thick with asbestos particles, Steve told John Sturges, that the men could hardly breathe.

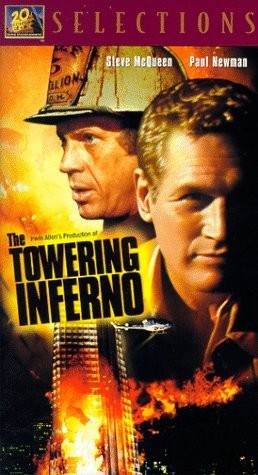

4. Conversations with Jim Hart, age 63, Northwestern, Arizona, a pleural mesothelioma survivor. Mr. Hart was a prop-maker and special effects production designer in Hollywood from 1971 to 1999. Mr. Hart worked with and around asbestos fibers during the creation of movie sets (joint compounds and plaster). Asbestos was also used in Hollywood for theatre curtains, artificial snow, ceiling acoustics, and fire retardant clothing (worn in particular by stunt men). Mr. Hart worked on several studio sets with Steve McQueen. While working as a prop-maker, Mr. Hart enjoys telling the story about the time in 1974 he "shared a couple of brews" with McQueen during the filming of The Towering Inferno at the "Fox Ranch" facility in Malibu Canyon. McQueen was on the set with a clutch of his buddies, and being the "man's man" that he was, he had a galvanized tub packed with ice and beer. Mr. Hart and his crewmates were working where McQueen and his friends were drinking. McQueen, renown for his rugged self-reliance and rebelliousness, invited Jim and his crew over to have a brew and yuk it up. Mr. Hart recalls that unlike a lot of Hollywood "A" actors, McQueen didn't mind getting his hands dirty. He noticed that McQueen was every bit as dusty and dirty as he and his crew were.Mr. Hart speculates that McQueen was likely exposed to many of the same asbestos materials he worked with and around daily.

Roger Worthington

rworthington@rgwpc.com

October 27, 2006

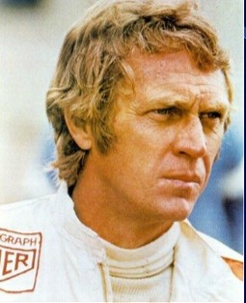

(1) de Lourmel, Lion Andre, photographer. Le Mans. Lee H. Katzin, Director. 197

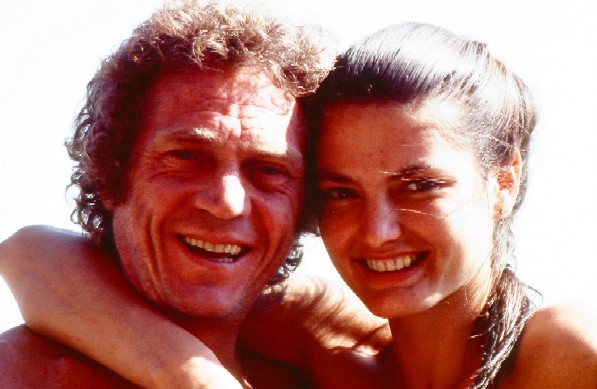

(2) http://www.mcqueenonline.com/mcqueenmintyarticlep1.htm. Woman's Own. March 29 1980.

(3) Photograph courtesy of Barbara McQueen.

(4) Friedman, Dave, photographer. Tom Horn. Wiard, William, Director. 1980.

(5) McQueen, Barbara and Marshall Terril. Steve McQueen: The Last Mile. Dalton Watson Fine Books. Deerfield, IL. 2007.

(6) The Towering Inferno. John Guillermin and Irwin Allen, Directors. 1974.

*** POSTED ON OCTOBER 31, 2006 ***